As I reflect on a year shaped by my Global Warming exhibitions, ongoing art-historical research, and my lecture in Switzerland last May marking J.M.W. Turner’s 250th birthday, I end the year thinking about an exhibition I visited last week at London’s Tate Britain:

Turner and Constable: Rivals and Originals

The title invites visitors to choose a winner. Unsurprisingly, early press coverage—across Britain and in France, Italy, and Spain—quickly adopted a competitive tone.

Three years ago, I was told that Tate had decided on a single exhibition to mark both artists’ 250th birthdays. I remarked then to the Senior Curator that this felt like a “two-for-one” marketing solution. In truth, Tate could easily have staged two major, independent exhibitions—one for each artist—on successive years, each drawing large and appreciative audiences.

Both Turner and Constable are towering figures of nineteenth-century British art. This exhibition includes many beautiful and inventive works, including important loans. Yet the framing does them both a disservice. The persistent question—who is winning?—gets in the way of deeper understanding.

Missing Constables

From the outset, the competition feels skewed. Key works and entire themes are missing. Stranger still, few visitors seemed aware that a second, free Turner–Constable display was running simultaneously in the Clore Gallery, elsewhere in the same building.

Confusion was audible. A man from Suffolk protested that “Turner’s been set to get Constable, even though we all know he was the most talented painter.” A woman lamented that her favourite Turners—The Fighting Temeraire and Salisbury Cathedral—were absent.

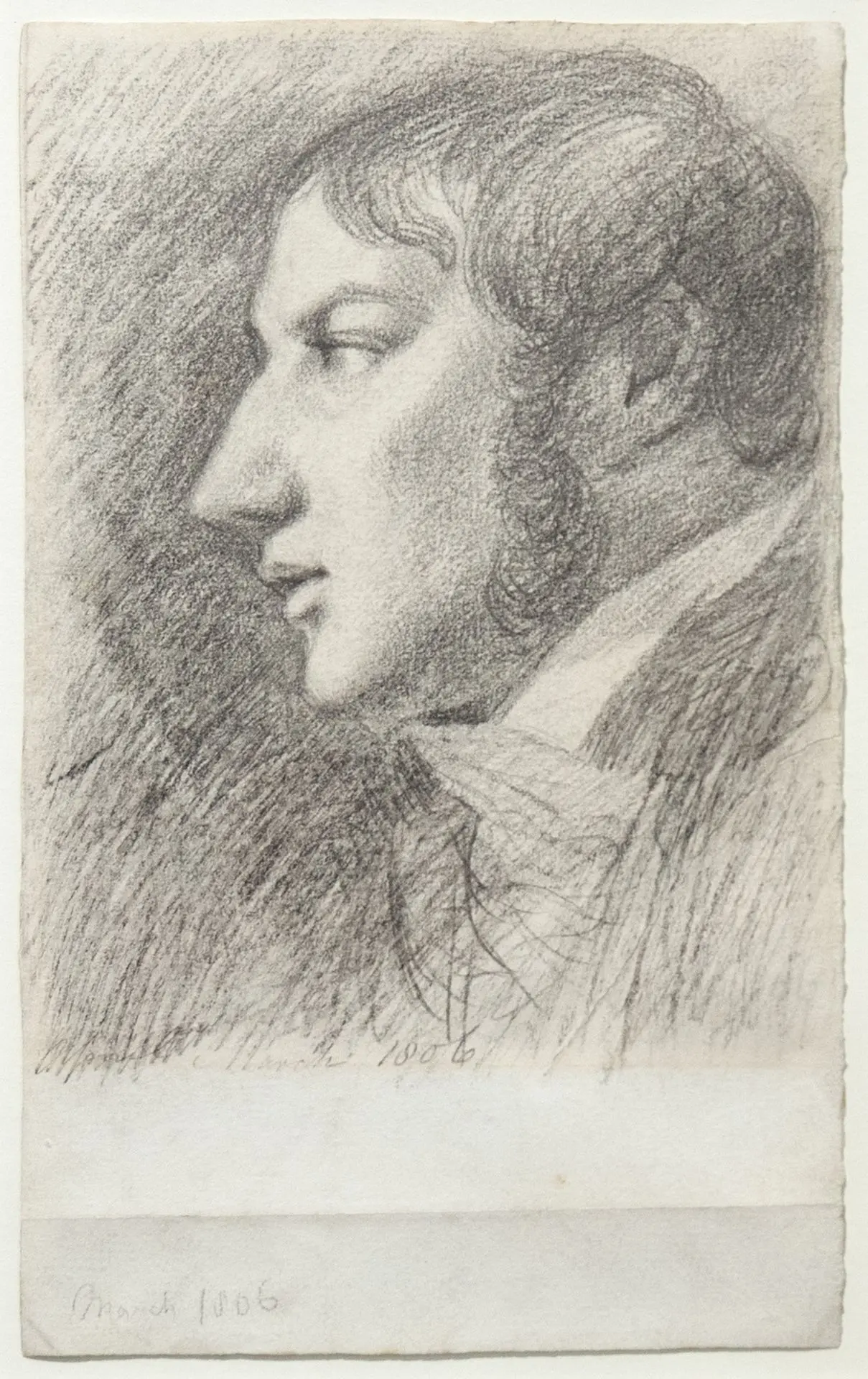

Constable fares particularly poorly. His portraits are almost entirely excluded, apart from a single self-portrait. This omission strips away an essential dimension of his artistic and emotional range. The tender July 1816 portrait of Maria Bicknell, painted when they were finally free to marry, would have added immeasurably to the narrative. So too would his delicate drawing of the young Maria (T03900), the tiny oil of Maria with two children (N03903), and his 1805 pencil self-portrait (T03899).

These absences obscure a fundamental truth: portrait commissions were not only artistically significant for Constable, they were vital to supporting his growing family.

Also missing is any meaningful account of the crucial role played by Archdeacon John Fisher—artist, confidant, and patron—whose influence shaped Constable’s Salisbury works. Tate’s label notes the Bishop’s objection to the dark cloud over the cathedral spire, but fails to explain that Constable painted the scene three times on identically sized canvases, refining it with each iteration, culminating in the magnificent version now at The Frick. None of these contextual developments are visible here.

Equally absent are Constable’s prints and the developmental stages of Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (1831), where collaboration with the lithographer John Lucas led to important refinements—though not to a revised oil painting.

Missing Turner

Turner, too, is incompletely represented. His extensive Continental travels—producing thousands of sketches and accounting for roughly a third of his career—are barely acknowledged. Many visitors will be surprised to learn that Turner travelled through present-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Monaco, Liechtenstein, the Czech Republic, and even what is now Poland (Szczecin). Nothing in the exhibition conveys this scope.

Works that might have helped balance the narrative—such as The Opening of the Wallhalla (1842) and The Bridge of Sighs (1840)—remain in the Clore Gallery. None of Tate’s superb watercolours for Samuel Rogers’s Italy and Poems appear, despite their enormous commercial and artistic importance. Turner’s vignettes made him Britain’s most sought-after illustrator and contributed significantly to his financial independence.

A False Rivalry

The rivalry itself is overstated. Rather than staging a contest, the exhibition could have shown how both artists transformed landscape painting in radically different—and fundamentally incomparable—ways.

That said, the works on display, both loans and Tate holdings, are of exceptional quality, making this a must-see exhibition. Yet each artist deserved his own dedicated exhibition to mark his 250th birthday, with a fuller and more balanced selection.

Visitors should not miss the additional Turner–Constable material in the Clore Gallery—though directions may be needed, despite it being in the same building.

A Personal Reflection

As my plane carried me home via Geneva, I thought of Turner’s many Swiss subjects and his expansive European vision. Yet I also felt a pull of homesickness for Constable’s Salisbury—where our son was born and christened in George Herbert’s little church, where our daughter attended Leaden Hall School, and where John Fisher’s house stands in the Close, at the end of the rainbow. Salisbury was also where my own artistic career began, teaching Art & Design at Bishop Wordsworth’s School and South Wilts Grammar.

Turner and Constable: Rivals and Originals is on view at Tate Britain until 12 April 2026.